Every Swift error you throw serves four audiences at once: users, your catch blocks, the debugger, and Sentry. We have a pattern to deal with all of them.

Tom Lokhorst, Mathijs Kadijk

tldr; Make one enum per service, conforming to LocalizedError and CustomNSError. This gives catchable cases for your code, localized messages for users, stable error codes for Sentry.

Errors aren't just for logging failures, they're a communication tool. When we recently improved error handling in our iPhone mirroring app Bezel, we found that every error serves four distinct audiences:

Each has different needs, and a well-designed error type can serve them all.

Create an error enum per service or module, conforming to LocalizedError and CustomNSError. This pattern handles all four audiences well.

enum LocationServiceError: Int, LocalizedError, CustomNSError {

case missingAuthorization = 1

case locationOutsideSupportedRegion = 2

case serviceUnavailable = 3

// LocalizedError - for end users

var errorDescription: String? {

switch self {

case .missingAuthorization:

return String(localized: "Location access is required")

case .locationOutsideSupportedRegion:

return String(localized: "Location must be within supported region")

case .serviceUnavailable:

return String(localized: "Location service is currently unavailable")

}

}

}

The Int raw value gives explicit error codes for free. CustomNSError uses rawValue as the error code and derives the domain from the type name automatically.

If you need associated values on your error cases, you'll need to implement errorCode manually. See our post on SDK error design for that pattern.

Let's walk through how this pattern serves each audience.

End users need localized, understandable messages. They should not see technical details like error codes or type names.

Any error you throw can potentially end up in your UI. Swift errors usually aren't typed, a throwing function just says throws, not which specific errors it throws. Therefore we always implement LocalizedError on our error types.

Conform to LocalizedError and implement errorDescription:

struct ProductsAPIError: LocalizedError {

var errorDescription: String? {

String(localized: "Unable to load products")

}

}

Now localizedDescription returns your custom message. This works for both structs and enums. The errorDescription property returns a localized string, so it will display in the user's language.

Without LocalizedError, users see the default system message, which isn't helpful. If you create a minimal error struct and display its localizedDescription:

struct ProductsAPIError: Error {}

// User sees: "The operation couldn't be completed. (MyApp.ProductsAPIError error 1.)"

Your code needs to catch and handle specific errors. This is where enums really shine compared to structs.

With an enum, catching becomes flexible. All errors of a type can be caught at once:

do {

try locationService.getCurrentLocation()

} catch is LocationServiceError {

// Handle any location service error

showLocationErrorAlert()

}

Or catch specific cases when you need different handling:

do {

try locationService.getCurrentLocation()

} catch LocationServiceError.missingAuthorization {

requestAuthorization()

} catch LocationServiceError.serviceUnavailable {

showRetryButton()

}

Think of the enum as the "domain" and each case as an "error code", similar to how NSError works. This gives both grouped and granular catching from the same type.

With structs, you lose this flexibility. If you had three separate structs instead:

struct MissingAuthorizationError: Error {}

struct LocationOutsideSupportedRegionError: Error {}

struct ServiceUnavailableError: Error {}

You'd have no way to catch them all at once. You'd need three separate catch clauses every time, even when you want to handle them the same way.

For older frameworks without Swift error types, like the Security framework (Keychain), match on NSError domain and code:

do {

try saveToKeychain(password)

} catch let error as NSError where error.domain == NSOSStatusErrorDomain

&& error.code == errSecDuplicateItem {

// Handle duplicate item error

}

Use enums for your error types. Each case becomes a distinct, catchable error, and you can catch them grouped or individually as needed.

When debugging, you want technical details, not localized user messages. The good news: this works well by default.

Printing an error shows the case name:

print(error)

// Output: serviceUnavailable

If you need a string representation for logging, cast to NSError and use debugDescription:

import os

let logger = Logger(subsystem: "com.example.app", category: "location")

do {

try locationService.getCurrentLocation()

} catch {

logger.error("\((error as NSError).debugDescription)")

// Logs: MyApp.LocationServiceError.serviceUnavailable

}

Don't implement CustomStringConvertible or CustomDebugStringConvertible on errors because it tends to lose information. The default representation already includes the type name and case, which is exactly what's needed for debugging.

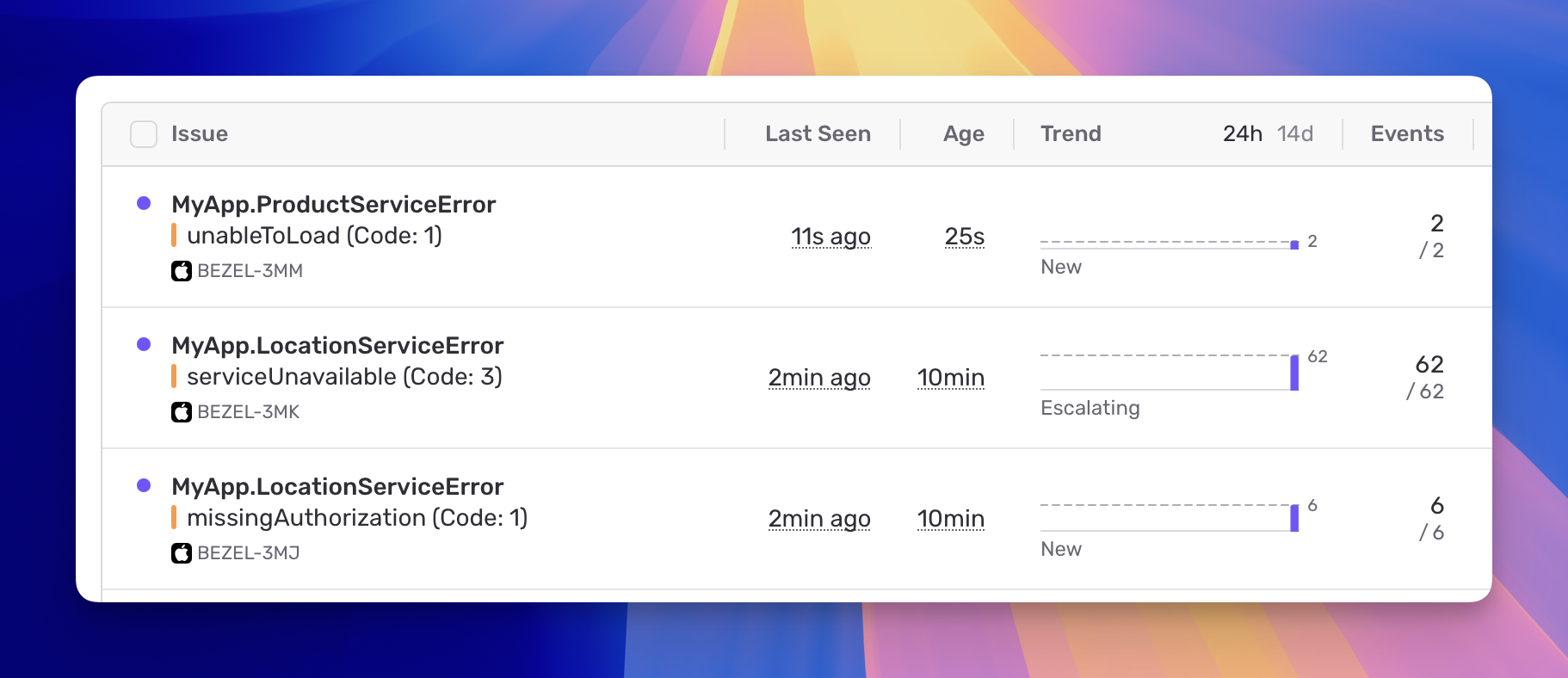

Systems like Sentry group errors by NSError domain and code, not by the localized description. This is useful: "Geen internetverbinding" (Dutch) and "No internet connection" (English) will group together as the same error.

Swift errors automatically bridge to NSError, but the auto-assigned error codes are problematic. They're based on Swift's internal enum layout, not declaration order. Cases with associated values are numbered before cases without. Adding a case or changing associated values can shift all codes, breaking Sentry groupings.

That's why we implement CustomNSError with explicit error codes in the example above. Your codes stay stable even as your enum evolves.

With explicit codes, each case gets its own stable error code, so missingAuthorization, locationOutsideSupportedRegion, and serviceUnavailable are grouped separately in Sentry, even though they share the same domain.

To serve all four audiences:

LocalizedError with errorDescription(error as NSError).debugDescription when you need a stringCustomNSError with explicit, stable error codesCreate a separate enum per service or module. For example: LocationServiceError, NetworkServiceError, StorageError. This creates logical groupings in your monitoring dashboard and keeps error handling focused.

We don't like to create one giant app-wide error enum like enum MyAppError. There's no benefit since errors in the app are already known to be from the app. Instead, start small: when an error is needed in a service, create an enum with the one case needed. Add more cases as needs grow.

Note: SDK development has a fifth audience: the app developers using your SDK. They need stable, documented error codes as part of your public API. We cover that pattern in a separate post.